The Second Blessing: Columbus Medicine and Health The Early Years

The Second Blessing: Columbus Medicine and Health The Early Years is a book written by Medical Heritage Center scholars Charles F. Wooley and Barbara A. Van Brimmer.

The Second Blessing: Columbus Medicine and Health The Early Years is a book written by Medical Heritage Center scholars Charles F. Wooley and Barbara A. Van Brimmer.

This digital exhibit of the book showcases each chapter. Copies of the book are available for purchase.

Acknowledgement: This exhibit was made possible by the generous support of Julia Metzger in honor of her father, Paul Metzger, MD.

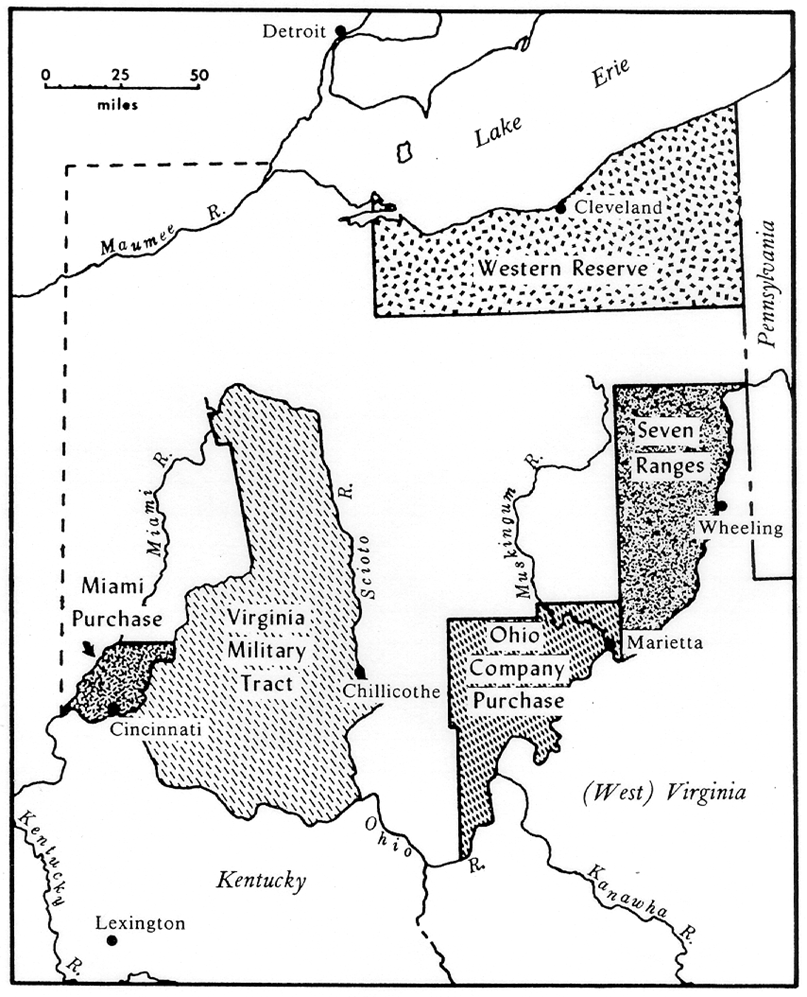

The U.S. Continental Congress in 1787 established the first colony of the United States—The Territory of the United States Northwest of The River Ohio—which later came to be known as the Old Northwest. It set up the beginnings of government of a vast region comprising 265,878 square miles of prairie plains and central lowlands that would yield five states: Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of a sixth—eastern Minnesota.

The emergence of Ohio as a state came about early in the existence of the Northwest Territory. Lake Erie on the north and the Ohio River to the southeast and south were the major natural geographical boundaries. The eastern and western boundaries were straight lines drawn—and later redrawn—by committees as Ohio was carved from the Northwest Territory. Geographical divisions of the Ohio Country within the general outlines of the state gave rise to new districts with new boundaries. These divisions became important factors in determining who would settle where within the emerging state.

|

|

Northern-tier medical colleges that developed in western Massachusetts and upstate New York in the early 1800s were staffed by local physicians and itinerant professors. These schools were forerunners of the Willoughby Medical College of Lake Erie in northeast Ohio. In 1843, after the college was involved in a scandal, several professors left Willoughby. They formed the nucleus of a new medical school at the Western Reserve College of Hudson, Ohio. Willoughby Medical College of Lake Erie closed in 1847, when the school transferred to the capital city with a new medical-college charter, some of the faculty members moved to Columbus (Willoughby University of Lake Erie Records 1834–1848).

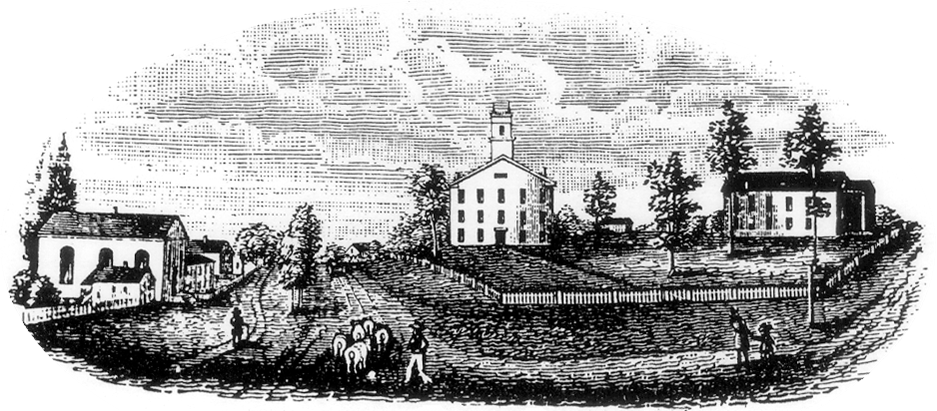

The founder of Franklinton, the first settlement on the Scioto River adjacent to the future town of Columbus, was Lucas Sullivant. His legacy as the central figure in the development of central Ohio, and the influence of his three sons—William, Michael, and Joseph—extended from the earliest days of settlement until late in the nineteenth century when The Ohio State University was established in Columbus.

Lucas Sullivant's brother-in-law Lyne Starling came from Kentucky to Franklinton to work with Sullivant. He became a successful merchant and was a prime mover in the political maneuvering that led to the selection of Columbus as the state capital in 1812.

Starling possessed a clear vision of the long-term need for a medical-college and teaching-hospital arrangement at the hub of community medical care. He then donated a generous sum to Willoughby Medical College, which changed its name in 1847 to the Starling Medical College.

|

|

The period of 1825–1850 in Ohio history has been described as the “passing of the frontier”—a time when the last stages of frontier development gave way to a settled commonwealth. The population figures tell part of the story; the approximately forty-two thousand Ohio settlers in 1800 had escalated to eight hundred thousand by 1826, and approached two million in the census of 1850.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, medicine in the region retained many frontier characteristics. With the exception of smallpox—for which vaccination was available—most common diseases were essentially unavoidable. The rigors of hard work and exposure to the elements resulted in trauma, injuries, accidents, and illness. Most physicians were apprentice trained and practiced a rudimentary form of medical care. Remedies were primitive and the relationship between lack of sanitation and spread of disease was poorly understood.

By 1835, only 20 percent of Ohio’s practicing physicians were medical-college graduates. The majority of Ohio practicing physicians received most of their medical education by the preceptor system. Formal student preceptorship involved private instruction by a practicing physician over a three-year period; after receiving a certificate of proficiency from his preceptor, the student legally became a medical practitioner. The efficiency of the preceptor system was dependent upon the preceptor’s knowledge, teaching abilities, and access to medical texts and current medical information. The system was more efficient in settled regions of the country than in pioneer environments.